Energy Innovation Will Define the 21st Century

Energy has been a fundamental driver of human advancement across millennia. At the simplest level, having more energy—whether in its biological, chemical, thermal mechanical, electromagnetic or other forms—allows individuals and societies to do more. From this perspective, human history and its many contests among nations have in part reflected continuous efforts to develop, control and use energy of one type or another. Consider how Imperial Japan’s lack of oil played a role in its (ultimately self-defeating) efforts to dominate East Asia. Or how the Soviet Union’s energy wealth sustained what might otherwise have been an unsustainable political and economic system.

Energy innovation—including finding new and more efficient ways to generate and use energy—can also help to build and sustain empires. Britain’s coal-fired steam-powered mills, factories and ships propelled it to global dominance. To maintain U.S. international leadership in the face of growing competition, the Trump administration and Congress should work together to promote modern-day American energy innovation.

President Donald Trump and his team have already focused intently on energy and its role in America’s prosperity and security. They doubtless recognize that the oil and gas industry supports approximately ten million jobs, while the electric power industry accounts for about seven million. Between them, and discounting for possible overlap, these two sectors could account for roughly ten percent of American jobs in an overall labor force of 163 million. On top of this, the American Public Power Association reports that electricity sector jobs pay 50 percent above the national average, while the American Petroleum Institute says that earnings in oil and gas jobs generate three times the national mean wage. Trump regularly connects energy and jobs in his public statements.

Energy and electric power contribute importantly to the U.S. economy in many other ways as well. At the simplest level, energy and electricity drive everything else—without them, our manufacturing, transportation, agriculture and communications would shut down. Since this is an unlikely scenario, however, a greater concern is that higher energy costs make everything else more expensive, slowing growth. Lower energy costs make other activities less expensive, facilitating growth and individual opportunity. Relatively low energy costs likewise improve America’s international competitiveness in energy-intensive industries—witness the movement of some German manufacturing to the United States over the last decade.

Energy matters in U.S. national security policy too. America has pursued a decades-long strategic effort to ensure stability in the Middle East and to protect oil and gas flows that fuel not only our own economy but also those of our allies in Europe and East Asia, as well as the global economy. Some see this as an attempt to guarantee that specific hydrocarbon molecules reach the United States, and therefore hope that expanding domestic oil and gas production will allow America to reduce its imports, make the nation energy “independent” and obviate the need for U.S. engagement with the region. Yet, so long as the United States consumes oil and gas, and the Middle East sells them in substantial volumes through global markets, it will be impossible to disconnect our domestic economy from global oil and gas prices or from the security environment in the Middle East. And because a healthy economy is the essential foundation for sustained defense spending, something especially significant in an era of great power competition, the U.S. military depends in part on America’s continued access to adequate energy supplies at reasonable prices as well as open energy markets and a generally stable global economy.

While the president often refers to “energy independence” as a goal, the Trump administration has done well to search for a new concept, and a new vocabulary, to describe America’s energy policy objectives at home and abroad. “Energy dominance” is an initial step toward a new energy policy framework but moving further along that path will require serious thinking about America’s preferred destination, the most promising routes and the appropriate pace. Energy innovation should be at the center of this process.

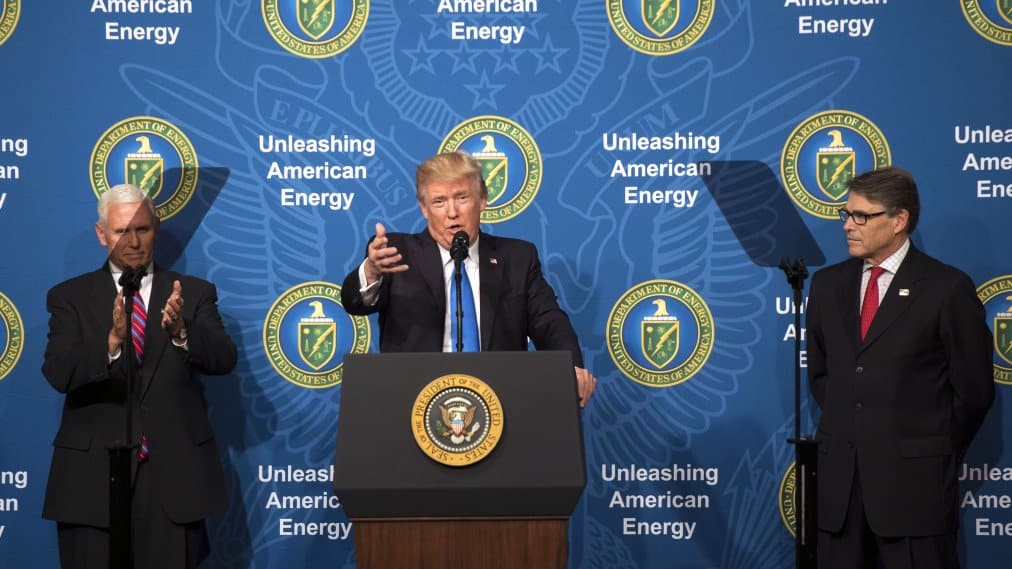

President Trump first articulated his desire for “energy dominance” in a June 2017 speech to business, labor and government leaders at the Department of Energy. In his remarks, the president called for maximizing U.S. energy production to create jobs, boost exports and “provide true energy security to our friends, partners, and allies.” He also announced several initiatives, including efforts to develop the domestic nuclear power industry and to promote new offshore oil and gas development, steps to simplify the financing of coal-fired power plants overseas, and approvals of a new oil pipeline and applications to export additional liquified natural gas (LNG). All seemed narrowly aimed at expanding growth and output in the energy and electricity sectors. Senior officials such as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Energy Rick Perry have since echoed President Trump’s emphasis on jobs and on energy exports to U.S. allies to buttress their energy security; for example, Secretary Perry has said that “the United States is not just exporting energy, we’re exporting freedom.”

Promoting growth in America’s energy and electricity sectors is a worthy goal. Yet pursuing growth in an extensive rather than an intensive manner—that is, doing more of what we are already doing, rather than continuously finding new and better methods—is not a sustainable strategy for achieving the national greatness that President Trump seeks. Nor is it adequate to ensure continuing economic growth.

First, U.S. domestic energy production, and specifically oil and gas exports, are not unlimited. BP’s highly-regarded 2019 Energy Outlook forecasts that the production of U.S. tight oil (the shale oil produced through hydraulic fracturing, or fracking) will peak in 2030, just over ten years from now. The U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook 2019 shows a similar peak in U.S. domestic crude oil production during the decade between 2030 and 2040. The point is not that America will use up its oil—a regular prediction that has repeatedly failed to come true as innovative technologies have unlocked additional resources—but that it would be irresponsible to ignore deliberate forecasting, or to count on specific technological achievements, in setting long-term strategy.

Second, other nations are pursuing intensive strategies in their own energy sectors, including China. While still behind the United States in research and development (R&D) spending, figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development show that Beijing increased its overall official R&D budget (including energy and other fields) by over 12 percent from 2016 to 2017, and now spends about 88 percent of what the United States does on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis. China still lags America in innovation, but it has caught up and even surpassed the United States in some areas, according to a 2019 report by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. In fact, according to the report, China secured fifteen times more U.S. patents for clean energy technologies in 2016 than in 2006. Complacence in competition is rarely the winning approach. Greater effort to promote U.S. energy innovation is the surest way to maintain the technological leadership that has been a foundation of American economic and military power.

The Trump administration is in a good position to pursue this approach based on its first National Security Strategy (NSS) released in December 2017. While brief in its treatment of the topic, that document defined energy dominance both more systematically and more comprehensively than the president and some other senior officials, characterizing it as “America’s central position in the global energy system as a leading producer, consumer, and innovator.” The NSS went on to assert that energy dominance “ensures that markets are free and U.S. infrastructure is resilient and secure” and that “access to energy is diversified.” Notwithstanding the president’s unfortunate public statements expressing skepticism about climate change, the NSS explained that energy dominance “recognizes the importance of environmental stewardship” and concluded on this topic with a call for investments in innovation and in research and development to protect America’s “long-term energy security future.”

Critically, the NSS places this approach to energy within a broader national security policy that is explicitly responsive to “the growing economic, political and military competitions we face around the world” and especially to the many challenges that China and Russia present to the United States and U.S. national interests. This is an appropriate and highly consequential departure from Obama administration national security strategies that focused primarily on global threats such as nuclear proliferation, terrorism and poor governance leading to arms and drug trafficking, refugee flows or the spread of infectious diseases. But as a strategy, it requires careful consideration of U.S. interests and how best to advance them at the least cost, of the nature and scope of twenty-first-century great power competition, and of how to employ America’s greatest strengths to prevail.

Competition between the United States and China is increasingly shaping international events and is simultaneously becoming more difficult for each government to escape. According to World Bank figures, China’s gross domestic product was about one-sixth larger than America’s in PPP terms in 2017, though approximately one-third smaller on an exchange-rate basis. Whichever measure one prefers, only China is an economic peer to the United States, though admittedly a peer with complex domestic problems and few reasons to expect the return of its past rapid growth. While relations between Washington and Moscow are worse, Russia’s economy is much smaller—either one-fifth (PPP) or one-twelfth (nominal) America’s. Fortunately, steps that strengthen the foundations of American power will help the United States to compete successfully with both China and Russia.

Despite conservative reluctance to accept any expansion in U.S. government spending or in the federal government’s role in the energy sector, at least since the end of the Cold War, it is indisputable that Beijing is vigorously backing China’s energy sector. China’s actions have included domestic investment, support for state companies at home and abroad, and theft or forced acquisition of U.S. and other foreign intellectual property, among other means. Perhaps the strongest testament to China’s unfair practices—and their costs to the United States and U.S. firms—is that the American business community has remained relatively silent as the Trump administration has pursued an expanding trade war with China, though many appear anxious over Trump’s handling of the dispute and some fear that he seeks to decouple the world’s two largest economies. Notwithstanding these concerns, U.S. companies today seem to have accepted that Washington cannot afford the economic policy equivalent of unilateral disarmament in competition with a near-peer. Among other steps, Washington would do well to create better conditions for U.S. firms to do what they do best: innovate and compete.

In a long-term U.S.-China competition, each nation will have to balance its domestic economic, political and social aims against the requirements of military rivalry, something that is easier for a more efficient and prosperous economy. Innovation will be a key aspect of this contest as it was during America’s Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. In view of energy’s role as a critical input across the American economy, energy innovation could have considerable multiplier effects for both America’s prosperity and its military capabilities. The competition to develop the new energy technologies that will power the future is one that America can and should win.

America has the tools to succeed in discovering, developing and commercializing new energy technologies. The U.S. private sector is large and robust, with extensive experience in key functions including research and development, financing and manufacturing. Moreover, according to the World Bank, America’s generally stable and efficient regulatory environment makes it one of the top countries in the world in ease of doing business—not to mention the highest-ranked large economy. Despite a downward slide in some international rankings, the U.S. education system continues to attract researchers and students from around the world. America has a strong track record in innovation and in energy, having developed foundational technologies including nuclear reactors, solar panels and, more recently, hydraulic fracturing. The United States also has an impressive array of seventeen National Laboratories within the Department of Energy conducting cutting-edge research, although some of these are focused primarily on supporting the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal.

And there are many promising technologies to pursue—some known and others doubtless still unknown. Advanced nuclear power, including small modular reactors (SMRs) as well as so-called micro-reactors that produce fewer than ten megawatts of electricity (enough to power roughly 2,000 households) could support efforts to deploy safe, clean and reliable electricity. Some advanced nuclear projects, like NuScale’s SMR, are increasingly well-developed; NuScale is preparing to build an SMR at the Idaho National Laboratory for Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems and expects the unit to be operating commercially by 2026. Micro-reactors could become especially attractive for military bases, isolated communities and other niche markets on a path to wider use. The Silicon Valley start-up Oklo’s micro-reactor—designed to be about the size of a shipping container—is technically impressive but further from operation than NuScale’s larger and more conventional design.

Despite setbacks, such as in Southern Company’s Kemper project, carbon capture, use and sequestration (CCUS) technologies continue to merit further exploration in view of growing global demand for low and zero-carbon electric power. For example, NET Power’s revolutionary Allam Cycle process uses fossil fuels to generate electricity while eliminating air emissions and producing nearly pure, compressed carbon dioxide that is discharged into pipes and suitable for industrial use or geologic sequestration. Other firms are exploring ways to capture carbon dioxide from the air and even experimenting with chemical processes to store captured carbon dioxide in manufactured stone construction materials. Considering the scale of existing U.S. and global coal-fired electric generation, the availability of coal as an inexpensive and energy-dense fuel, and America’s expanding reliance on natural gas, expanded CCUS research makes sense.

Energy storage technologies, especially batteries, are widely-discussed in the media given their essential role in facilitating extensive adoption of intermittent power sources like wind and solar energy and in powering electric cars. Lightweight and efficient energy storage could also have widespread military applications and accordingly has won close attention from the Department of Defense. Storage should be a higher priority too.

Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), also known as hot dry rock geothermal power, is among the lesser known technologies with the potential to transform the twenty-first-century energy landscape. Advances in drilling technologies and hydraulic fracturing may allow widespread adoption of a massive renewable power resource that has thus far been accessible (and economically viable) only in geologically rare locations. Much deeper drilling—up to and exceeding ten kilometers!—could radically change the business case for geothermal energy: a safe, sustainable, reliable and emissions-free source of energy. Among other opportunities: siting such systems at existing coal-fired generating plants might allow utilities to repower these facilities, using their existing turbines and other infrastructure, reducing costs, and helping utilities to avoid holding possibly stranded assets. Using supercritical carbon dioxide (rather than water) as the heat-exchange medium could simultaneously increase efficiency and decrease environmental impacts from EGS projects. These technologies merit greater attention and support.

The federal policy approaches available to promote energy innovation are not mysterious. Broadly speaking, the federal government can improve the regulatory environment for emerging technologies and can direct money towards them. For greatest effect, it should do both—modernizing, easing or streamlining regulatory procedures while providing expanded federal funding for energy-oriented research, development and demonstration of innovative technologies. The Nuclear Energy Leadership Act, introduced in the Senate in March, is an example of the former. Increasing the Department of Energy’s R&D budget substantially—in a technology-neutral manner—is a key element in the latter.

Conservatives are right to resist government attempts to pick winners and losers in the marketplace—that is the market’s role, and U.S. energy and power markets will generally be more efficient in making such selections. Nevertheless, they should also recognize that the federal government has a crucial role in defining national priorities, especially in the energy and electricity sectors, which are among the most highly regulated sectors in the American economy and seem likely to remain so. In other words, the federal government should not arbitrate among commercially-viable technologies (beyond what is necessary in maintaining a diverse and reliable power system) but should be able to support the development of technologies that might prove critical to the national interest, spurring growth and promoting American competitiveness. Of course, all of this requires accepting that some projects will fail; while greatly feared in politics and bureaucracies alike, failure is an inherent and even valuable part of both scientific discovery and entrepreneurship.

What America has lacked so far is a political consensus to assign necessary priority to energy innovation as a national-level goal. However, this may be changing, as Republicans increasingly feel public pressure to develop policy responses to climate change. A recent survey by Yale University and George Mason University found that 69 percent of Americans are “somewhat worried” and 29 percent are “very worried” about climate change; a University of Chicago/AP survey found that 48 percent of Americans say that their views on the issue have shifted in part due to experiences with extreme weather. Even absent any effect from recent shifts in public opinion, Congress has already twice (under GOP leadership) rebuffed Trump administration attempts to slash the Department of Energy’s research and development budget (perhaps partially to protect states and districts that benefit from the work) and seems likely to do so a third time during the fiscal year 2020 budget process. Congress has also passed helpful legislation such as the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act, which President Trump signed into law in January. In the 116th Congress, Republican leaders including Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee Chair Lisa Murkowski have signaled support for legislation to advance energy innovation. Nuclear innovation is especially important in that it can simultaneously promote domestic energy security and economic competitiveness, contribute to America’s international nonproliferation goals and U.S. exports, and help to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

Moreover, Republican support for policies to promote energy innovation—including increased spending on research, development and demonstration programs—seems likely to expand as national security conservatives increasingly consider key technology and other policy decisions within the context of U.S.-China competition. This has already begun to occur in information and telecommunications policy, where concerns about America’s slow adoption of 5G cellular technologies and about the national security implications of incorporating Chinese-sourced network equipment into critical communications infrastructure have intersected in producing simultaneous efforts to accelerate 5G deployment while excluding Chinese firms such as Huawei from the U.S. market.

The latter half of this dynamic is evident in the energy sector. A bipartisan group of eleven senators has asked the Departments of Energy and Homeland Security to consider banning Huawei from supplying solar inverters—which convert direct current from solar photovoltaic panels to the alternating current used in the electric grid—in the U.S. market. Considering simultaneous and longstanding frustration with China’s commercial espionage among American businesses and on Capitol Hill—which many see as a direct threat to America’s long-term success as an innovation economy—it would be quite surprising if technology does not soon emerge as a central front in the U.S.-China contest for global economic and political influence.

Moreover, a successful diplomatic resolution of the ongoing U.S.-China trade war seems unlikely to erase competitive tensions. U.S.-China competition has intensified over more than a decade, perhaps most dramatically in the wake of America’s 2007–2008 financial crisis, when Beijing appeared to become increasingly confident that America had begun a long-term decline and became more assertive. Indeed, from this perspective, a strong and innovative U.S economy may be among the most effective instruments of deterrence—it refutes the narrative that America is in decline, reinforces multiple dimensions of U.S. soft power and demonstrates the country’s ability to sustain a highly capable military force into the future—something that discourages rivals and reassures allies.

Yet while advocates of energy innovation may welcome U.S.-China competitive pressures as a force for bipartisan cooperation in an area of national consequence, the escalating competition between Washington and Beijing may have some undesirable implications too.

Most important, though robust competition can produce many benefits, unregulated competition among great powers can end quite badly. U.S. leaders should embrace competition as a call to action but should also take great care to avoid its darker forms. Allowing a U.S.-China trade war to produce a global economic crisis or, for that matter, allowing disputes in the South China Sea or elsewhere to produce a large-scale armed conflict, could be extremely costly. When possible, U.S. officials should continue to explore cooperation.

Intensifying U.S.-China competition in energy technology may be especially problematic for international cooperation to stop climate change. Combating climate change at the international level doesn’t necessarily require global treaties, however much some may want them, but does require the easy movement of investment and technology across national boundaries and especially into China, whose carbon dioxide emissions from energy consumption were nearly double America’s in 2016, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency. If the United States bans or limits Chinese energy technologies from “critical” areas in its domestic energy infrastructure and presses its allies to do the same (Washington is already discouraging governments from using Huawei 5G cellular systems), the free flow of investment and technology around the world seems likely to suffer. If these approaches take root, one could even imagine two rival technology blocs, each with its own standards and supply chains. Many governments would likely be loath to choose sides—and forcing them to do so could backfire, especially if China’s government did not attempt to discourage those buying its products from using America’s too. Whatever happens, the prospects for cooperative U.S.-China energy and climate research programs may dim, and soon.

Regardless of how U.S.-China relations may turn out, however, global energy markets are set to evolve substantially in the coming decades. The task for the Trump administration, and for Congress, is to ensure that the United States continues to innovate in ways that place America at the forefront of global energy development and transformation. That will help to bolster growth, increase competitiveness and guarantee the nation’s long-term security.