Over the last decade, the current political order in Africa has come under increasing challenge. In urban areas, what has been called a protest wave is coming to look more like a protest era. In various rural zones – from the Sahel to the eastern Congo and Mozambique – jihadist movements have multiplied and spread across borders.

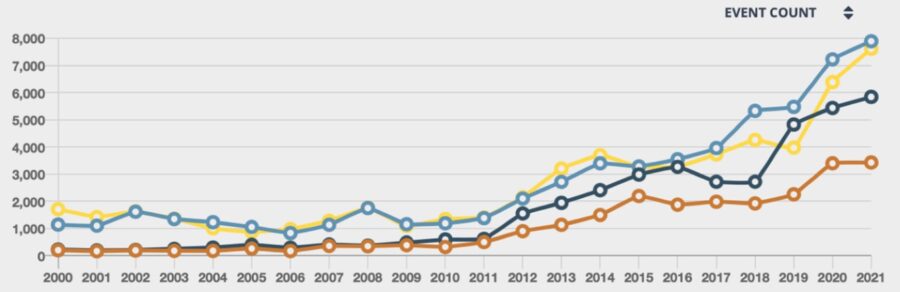

The data leaves little doubt about the expansion of political instability. According to ACLED, the number of protests in sub-Saharan Africa has soared from a mere 614 in 2011 to 5,900 in 2021. In the same period, the incidence of battles and violence against civilians increased by nearly 480%.

Why is this happening? And why now? The usual explanations of poverty and corruption are useful but only up to a point. These problems, after all, are hardly new. My research suggests that what we are seeing across Africa is not your run-of-the-mill instability. Rather, it is a sign that the entrenched patronage-based order, fragile in the best of times, has generated new and powerful adversaries that the system can no longer tame or absorb.

Numbers of incidents in sub-Saharan Africa since 2000. Light blue: violence against civilians. Yellow: battles. Dark blue: protests. Orange: riots. (Source: ACLED)

The patronage paradigm

Patronage politics of some variety is nearly ubiquitous across Africa. This is partly a legacy of colonialism. At independence, many states inherited countries that European imperialists had stitched together with little regard to the communities that would either be forced together or sliced apart by their arbitrary borders. To bolster their tenuous positions, regimes across the continent turned to some combination of repression and co-optation of elites. Rebellions would be violently suppressed, or their leaders would be bought off with state resources and a stake in the status quo. In some instances – such as the National Resistance Movement in Uganda – a bold reform movement took power through force, but nonetheless soon turned to patronage politics as a pragmatic way to govern themselves.

Though tumultuous at times, this manner of governing persisted comfortably until the 1980s when debt, recession, and conditional loans forced African states to shrink and privatise. With fewer state resources to go around, patronage networks suffered. Dissent, insurgencies, and conflict increased. Nonetheless, the system survived despite several single party regimes being forced to transition to multi-party democracy in the 1990s. After 2000 when commodity prices boomed, patronage politics stabilised and retained its effectiveness in withstanding and absorbing opposition.

Since the 2010s, however, something has shifted again. States have continued to use repression and patronage in the face of resistance, and yet the frequency of protests and insurgencies has only continued to rise.

A new protest era in the towns

In Africa’s cities and towns, protest is the chosen means of rebellion that the patronage paradigm has failed to capture and suppress.

There are numerous reasons for this trend. One is that these newer anti-regime mobilisations are being organised and led by individuals from a narrow middle-class. These activists are often privately employed outside the civil service or parastatal companies that previously absorbed this group. They are therefore insulated from patronage networks. They can rebel without biting the hand that feeds them and remain on the streets even after achieving short-term victories.

Thanks to the greater flow of money and ideas across borders in the 21st century, this generation of organisers and their movements are also more likely to be influenced by ideas and strategies seen elsewhere. They may be more idealistic and have significant access to the tools, knowledge and templates to channel mass grievances into action.

The motivations of these protests may also be different to their predecessors. Recent mobilisations are often responding to popular discontentment that growth hasn’t translated into economic benefits for most people and that successive governments have failed to live up to their promises of better governance. Their demands – unlike those in earlier eras, whether openly declared or not – are not to get more patronage for their supporters or take over the patronage-based system. In fact, several citizen movements – like Y’en a marre in Senegal, the Balais Citoyen in Burkina Faso, and the Sudanese Professional Association – have deliberately organised outside partisan politics in favour of exerting outside-in pressure. Lucha in the Democratic Republic of Congo goes as far as to forbid members from running for office.

Not all movements eschew formal politics. Bobi Wine and his People Power party have galvanised poor urban youth in Uganda. Peter Obi’s presidential campaign in Nigeria is harnessing the anger and hope of the youth-led #EndSARS movement. But the appeal of both figures is that they are regarded – rightly or wrongly – as leaders that, if elected, would bring an end to politics as it is.

What all this has led to is a rise of resistance that – for the first time – threatens the post-independence African political system itself. These social movements don’t rely on patronage networks and are not vying for greater inclusion within them. As such, regimes may still be able to turn effectively to heavy-handed repression, but they find it much harder bring an end to these waves of protests through co-optation.

A new era of rural insurgency

The dynamics described above have largely emerged around wealthier urban centres with middle-classes. The context is different in rural areas. As the CEO of a Congolese tech startup told me, “In Goma, there is money…young people engage in entrepreneurship”; outside, youth can only make a living through “politics” (i.e. patronage). In many countries, ruling parties that encounter resistance in towns have nonetheless managed to maintain complete dominance in rural areas.

These regions, however, have also seen a rise in mobilisations that are more immune to co-option and that threaten the patronage system. In countries from Mali to Mozambique, and from the Lake Chad Basin to the eastern Congo, jihadists have tapped into rural grievances to spark armed insurgencies. Like some urban social movements, these religious movements are also often led by relatively young, educated, and ideologically determined organisers who have lost faith in ineffective and corrupt states. They too are influenced and supported by ideas and funds from abroad – in their case, so-called Islamic State or Al-Qaeda.

These groups were typically founded as non-violent organisations but, after facing state repression and being inspired by the growing transnational jihadist movement, turned to armed insurgencies. While popular protest movements are most effective in densely populated cities, successful insurgency is almost always a rural phenomenon. Boko Haram’s urban uprising in 2009, for instance, was easily crushed by Nigerian security forces. The movement only grew after retreating to the periphery, winning over segments of communities frustrated with the patronage system, and waging an asymmetric campaign.

From these rural bases, jihadists seek the strength to defeat and replace the state, as we have seen at times in north-east Nigeria and northern Mali. While urban protesters seek to break the patronage system though accountability, jihadists promise to abolish states altogether in a great purge of the corrupt Western order. Once again, armed movements are far from new on the continent, but the crucial difference is that today’s Islamist militants do not want to control the system but abolish it.

New order

These new protesters and insurgents pose the most serious threat yet to an African political order that has remained in the grip of a toxic colonial legacy since independence. The outcomes of this challenge, however, are far from predictable or necessarily positive.

These challenges have pushed rulers into a corner in which they can neither co-opt their opponents nor give in to demands to dismantle the very system that keeps them in power. The only remaining tried and tested option therefore is heavy-handed repression. This response, however, further delegitimises governments and encourages further rebellion, sparking a vicious and unpredictable cycle. In Sudan, for instance, violence has not solved the junta’s problem but pushed it into a fragile limbo without effectively suppressing popular demands. In Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso, popularly backed coups have brought in military governments just as ineffective as their predecessors at quelling urban or rural rebellion. Protest, further coups, and jihadist gains are often the result of this cycle.

African states have developed an allergic reaction to the patronage-based connective tissue that holds regimes together. Failing to diagnose this problem can at best result in a tenuous purgatory of perpetual instability. Either way, the system is under unprecedented pressure and, while the change that will come will not necessarily be positive, it will also not necessarily be negative. With change comes hope and the promise of a new order. A revolutionary reimagining of African politics appears on the horizon.