By Abdalhadi Alijla /Open Democracy/ – Do people tend to trust non-corrupt and transparent institutions more than others in the Arab region? The logic says so, but the findings show the opposite.

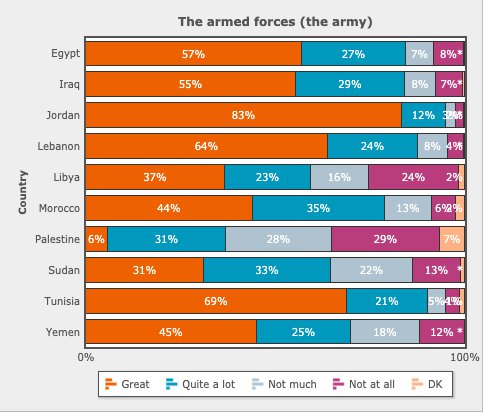

According to the Arab Barometer from 2018-2019, 49.4% of people in Algeria, Iraq, Palestine, Jordan, Tunisia, Morocco, Kuwait, Sudan, Lebanon, Egypt and Yemen have a high level of trust in their armed forces, while 26% have quite a lot of trust in their armed forces. In the same survey, 47.3% of respondents who said that they have a high level of trust in the armed forces replied by saying that there is a very high level of corruption at the national level in their countries, while 52.2% of them said there is an average level of corruption at a national level.

For instance, in Egypt in 2018, 57% of Egyptian respondents said that they have a high level of trust in the army, while 27.3% had quite a lot of trust in their armed forces. Strikingly, 48% of respondents who said that they have a great level of trust in the army believe that corruption in the country is extreme. The majority of the surveyed people tended to believe that there is corruption to a large extent at the national level (formal institutions): 74% of Iraqis, 59% of Lebanese, 77% of Libyans, 42% of Moroccans, 46% of Sudanese, 74% of Tunisians and 33% of Yemenis.

Based on data from the Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), which measures five corruption risk factors: political, personal, operational, financial and procurement, the great majority of MENA countries have a high level of corruption risk. GDI categorizes corruption risks from A to F, where F is the highest corruption risk, and A is the lowest. Most MENA countries are at a critical or very high level of corruption risks.

Algeria, Jordan, Egypt, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia suffer from critical corruption risk in their defense sector, while Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, and UAE suffer from high corruption risk in their defense sector.

Compared to the data from the Arab Barometer, we find that the countries with critical corruption risk have high level of trust in the army. For instance, in Tunis, which is the only MENA country which scored a “D”, 69% have trust in the armed forces, although 74% of them believe that there is corruption in no small extent in the country. Tunisia’s level of corruption risks indicating a slight improvement in the defence sector.

This contradictory attitude to corrupt institutions which have been abusing power, exploiting economy, evading scrutiny and oversight under pretexts of confidentiality and national security bring us to the puzzle of why people tend to trust what they perceive as corrupt. Do they prioritize security? Heroism? Militarism?

Do citizens even know about the corruption within the defence sector, or do they prefer to turn a blind eye, as the army is the most powerful institution in the country? Indeed, many know about the corruption in the military, but do not speak out because they may face extreme punishment. Subsequently, media would not cover corruption cases, allowing masses to know about these practices.

The glorification of the army, selling it as the saviour of the nation from external and internal enemies, appears to work as a strategy of manipulation

The data demonstrates that the perception of corruption at a national level in MENA countries does not include the defence sector and the armed forces. The high levels of trust towards the armed forces compared to other political and judicial institutions reflects a contradiction in the perception of corruption. It seems that citizens in the MENA region exclude the army from their perception of corruption, perceiving it as a separate entity from the government, parliament and judicial. The perception of the armed forces as a unique institution means a trust gap between civilian institutions and military institutions in the region. The glorification of the army, selling it as the saviour of the nation from external and internal enemies, appears to work as a strategy of manipulation. Civil-military relation in MENA should be examined by asking how the military is being presented to the public through media.

One significant component of the GDI is the accessibility of information about the defense sector. According to GDI, all MENA countries (except Tunis) have extreme confidentiality on their data, which do not give media, journalists and CSOs the possibility to criticise the military. Local media are prohibited (by law in most MENA countries) to publish any data on the defence sector as it is considered confidential, and in most cases undermines national security. However, there are possibilities to reveal corruption practices within civil institutions. In most cases, these corruption scandals are used as a political tool to gain public support, such as in Lebanon.

In divided societies and politically polarised states (such as in Lebanon, Tunis, or Iraq), the military utilises a corporate national identity. In these cases, the army presents itself as an entity that unites all the factions, and sects. There is a weighted effort by the military to present itself as the guard of unity that brings all sects and colours of the society together. Such a strategy aims to present the army to the people as a model among the failing civilian institutions, protecting the stability of the country. The process of creating a corporate national identity comes either through the experience of civil war or a professional military. For example, in Egypt, the army presents itself with a corporate national identity as the saviour of the people, providing security, fighting terrorists and also providing affordable goods to civilian markets.

In conclusion, the level of trust in the armed forces is a result of long strategies that include the creation of national corporate identities, while preventing and punishing accessibility of information and lack of openness towards the people. Although there is a high level of trust in the armed forces, the figures do not mean that there is no corruption within these armies, rather it indicates a very wide gap between armies and citizens.