‘He achieved nothing’: Bitter legacy of Tunisian vendor who sparked uprising

Mohamed Bouazizi wasn’t any different than the hundreds of other downtrodden young men in this small and dusty town which is surrounded by scrub and cactus.

Many of them had university degrees but either couldn’t find work or were forced to toil away in the olive groves, working under the blistering hot sun for less than $3 a day.

But what Bouazizi did have was a cart.

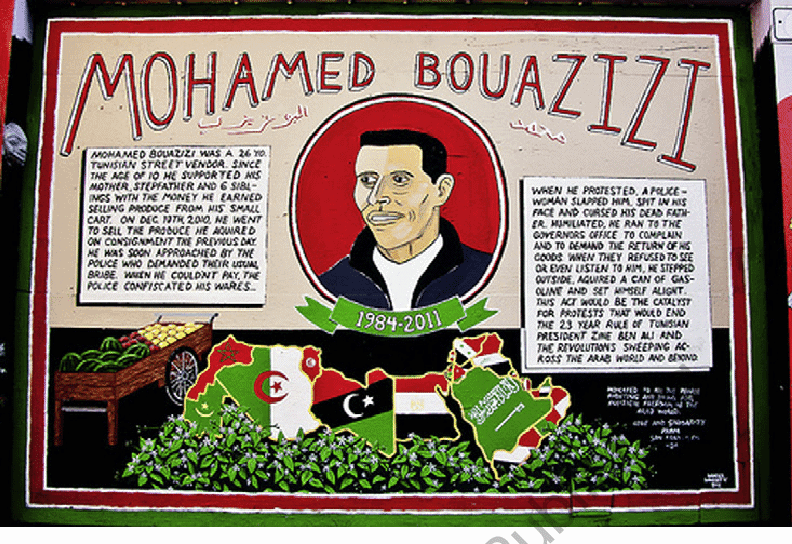

The 26-year-old sold fruit and veg throughout Sidi Bouzid since he was 19, earning enough to provide for his family of eight and keep his five younger siblings in school.

But on 17 December 2010, his livelihood was threatened when a policewoman confiscated his scales and produce.

According to Bouazizi’s maternal uncle, Ridda, local police had been picking on his nephew for years.

“Whenever he would go to the souk, officers would fine him for running a stall without a permit,” he said.

At 10 o’clock that morning, the harassment crossed a line.

A policewoman slapped him, spat in his face and insulted his deceased father when he failed to pay a fine.

Publicly humiliated, Bouazizi went to the local municipality to try and seek recourse.

Instead he was told to leave, as the most senior official there was busy in a meeting, an excuse Ridda says locals were accustomed to hearing.

Bouazizi left but returned an hour later. At 11:30 am, the dispirited street vendor doused himself with paint thinner and set himself alight in front of the building.

The self-immolation sent the town into a frenzy, sparking a popular revolt against the cloying authoritarianism of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali.

Within four weeks, Ben Ali’s 23-year grip on power was over and the autocrat fled to Saudi Arabia.

In the weeks and months that followed Bouazizi’s death, the street vendor became a symbol of the disenfranchised – those who were forced to eke out a living on the margins of society.

However, despite capturing the imagination of millions of Tunisians and countless others, his legacy is now being questioned.

‘What’s really changed?’

At the souk in the centre of town, just a mere mention of his name evokes a frosty response from several street vendors, including members of his own family.

“Mohamed was a good boy, and he did what he felt was necessary,” his uncle Ridda, 45, told Middle East Eye.

“But none of the people [in Sidi Bouzid] have gained anything from his death. He achieved nothing.”

That view was echoed by Shuaib al-Qadri, a 57-year-old market trader who said it was unlikely he would retire before reaching 65.

“I knew Mohamed since he was a child, he used to play with my children, and I was deeply saddened by his death. But in the years since [his death] what’s really changed? We’re all still drowning in poverty.”

According to government officials, more than 600,000 families across Tunisia cannot meet their daily needs, and disparities between the impoverished interior and its relatively prosperous coastline remain unaddressed.

The unemployment rate in Sidi Bouzid is also around three times higher than that of coastal areas, according to the IMF, with the unemployment rate among under 24-year-olds at more than 30 percent.

“Corruption persists,” said Hisham, a 37-year-old who was passing through the souk.

Young people still have to pay a bribe if they want to work in the public sector.

“I’ve been working as a civil servant for the past nine years and all I get is 400TD ($140) a month,” he said.

“The revolution has failed the people. How can I or anyone afford to live a comfortable life with that amount? We can’t pay our bills and give our children a better life than what we had. We can’t.”

The Bouazizi family has also had to contend with allegations that they dishonoured their son’s memory after allegedly receiving large sums of money from the government, a claim that has yet to be proven.

Bouazizi’s mother, Manoubia, and her children first left Sidi Bouzid for La Marsa, an upscale suburb in Tunis, in 2011, before moving to Montreal in 2015.

Many have also felt frustrated that their struggle has been reduced to the story of Bouazizi, rather than the collective uprising during which 219 Tunisians lost their lives.

“The revolution uncovered a lot of wrongdoings and for this we have to be thankful to Mohamed,” said Ali Bouazizi, a cousin of Mohamed and head of an NGO which supports local unemployed people in setting up their own businesses.

“Nepotism and corruption haven’t gone away. Our demands are still ongoing, and the people are still resisting.”

‘A matter of national security’

Millions of Tunisians are expected to head to the polls on 15 September in the second free presidential election since the revolution.

On 8 September, during the first of three televised debates between the 26 hopefuls, Islamist candidate Hamadi Jebali, the country’s prime minister from 2011-2013, renewed his pledge to stamp out corruption should he win Sunday’s poll.

“Corruption is a matter of national security and clear legislation is now needed to prosecute those who engage in it,” he said.

While just under three million Tunisians, or around 30 percent of the population, tuned in to watch, statistics show that voter apathy is on the rise.

The turnout for local government elections last year was at 34 percent and came on the heels of widespread protests over living standards.

According to a recent poll by the International Republican Institute, a growing number of Tunisians have become pessimistic about the electoral process with only 31 percent saying they were very likely to vote.

More Tunisians said they saw the country headed in the wrong direction than at any time since 2011.

Analysts have said it is unlikely any of the candidates will obtain a majority, meaning a second round of voting could take place in November.