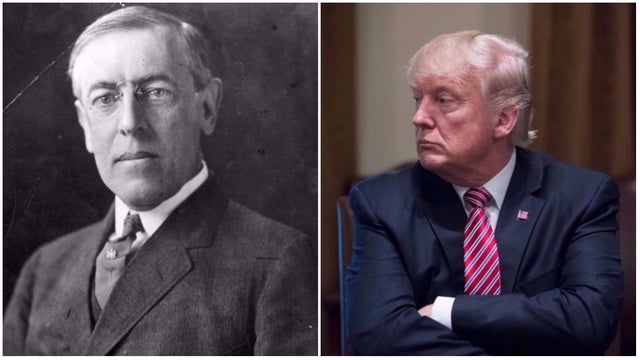

The End of the Wilsonian Century?

One hundred years ago this fall, the U.S. Senate debated whether to enter into a new League of Nations championed by then-president Woodrow Wilson. In Wilson’s mind, the League was meant to be the capstone for American leadership of a liberal world order.

Today, the Trump administration’s critics worry that the United States has become the leading opponent of that same liberal world order. But the administration’s most fervent critics misunderstand its foreign-policy approach, along with multiple U.S. diplomatic traditions.

The Trump phenomenon does indeed represent a resurgence of American nationalism. American nationalism, however, is not incompatible with certain forms of U.S. engagement overseas. The real question is, and always has been, the exact form of that engagement.

Fundamentally, a close attention to U.S. freedom of action and material American interests is no scandal. The true starting point of U.S. foreign policy is not to promote rules-based liberal world order through multilateral institutions, as such. Rather, the true starting point for US foreign policy is to promote the interests, security, prosperity, principles, and self-government of U.S. citizens. Other worthwhile American commitments—including those in favor of pluralistic regional systems abroad, along with specific U.S. alliances—follow from that starting point.

Liberal internationalists insist that American engagement abroad be on liberal or Wilsonian terms. But the Wilsonian internationalist vision, especially in its post–Cold War iteration, contains some very serious flaws that helped lead to Donald Trump’s election in the first place.

Unless and until today’s Wilsonians grapple with these realities convincingly, there is no sign that Trump’s appeal for a great many U.S. citizens will dissipate.

Wilsonian Visions

Within the United States, the liberal internationalist or Wilsonian vision developed in three great waves.

The first U.S. liberal internationalist wave developed during and immediately after World War !. Woodrow Wilson’s vision was that U.S. entry into war against the Kaiser’s Germany would usher in a new world order characterized by global democratic government, economic interdependence, mutual disarmament, and collective security. This last feature, in particular, was to be secured through a new League of Nations, in which every member state would promise to protect the independence of every other state by force if necessary.

American hopes for the spread of popular self-government overseas were of course nothing new. The nation’s founders had spoken of this often. But the founding generation of the United States, along with several generations after, also took it for granted that American national sovereignty was to be cherished and preserved. They saw no contradiction between that determination, and hoping for the spread of republican forms of government internationally.

Wilson’s great innovation, therefore, was not to aim for the spread of democracy. Rather, his great innovation was to insist that only through global, binding, multilateral commitments could American democratic values be safely promoted abroad.

Most Republican U.S. senators at the time, led by Henry Cabot Lodge Sr. (R-MA), did not disagree with postwar U.S. security commitments toward key European allies such as France and Great Britain. In fact, to a greater extent than Wilson, they favored such commitments. However they refused to believe that the United States had an equally vital interest in the material defense of every single nation on earth, and for this reason they opposed Wilson’s League in the absence of significant revisions. Refusing to compromise on this point, Wilson lost his vote in the Senate, along with U.S. membership in the League. Wilson failed in the short term. But in the long haul, he laid down ideological markers that would prove to be exceptionally powerful.

The second Wilsonian wave developed during and after World War II. Under presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, the liberal internationalist vision was resuscitated and put forward in new form. Both of these Democratic presidents framed their foreign policies in part as attempts to vindicate hopes for a more open and humane world order, and there is every sign that they meant it. But their 1940s version differed from Wilson’s in several significant ways. Both FDR and Truman were more politically adroit than Wilson in recognizing and responding to domestic political critics. Valid Republican concerns were often factored into presidential foreign-policy proposals, rather than rejected out of hand. The political mood within the United States had changed to the extent that more Americans were willing to consider truly dramatic departures in U.S. foreign policy. The terrifying spectacle of fascist aggression followed by Soviet Communist expansion constituted a powerful real-world argument on behalf of greater U.S. engagement overseas. This was no abstract case for global governance. Rather, it rested on the concrete existence of totalitarian and genuinely threatening great-power adversaries bent on competition. And the United States of the 1940s possessed unprecedented material capabilities to act on the above concerns.

Together, FDR and Truman launched a major shift in U.S. foreign policy. Yet in reality, neither of them entirely rejected traditions of American nationalism. In some ways they built upon those traditions. In their plans, the United States retained considerable leeway for freedom of action, whether unilateral or bilateral, diplomatic, military or economic. And unlike Wilson, both FDR and Truman grasped the central geopolitical challenges of their presidencies instinctively. In this practical manner, as opposed to dogmatically, they addressed the particular challenges of their day.

The third Wilsonian wave developed after the end of the Cold War. Confident that history itself might have ended, liberal internationalists now argued that a combination of multilateral institutions, conflict resolution mechanisms, humanitarian interventions, worldwide democratization, and global governance projects would render traditional patterns of power politics irrelevant. Post–Cold War Wilsonians on the right—while more realistic about the limits of multilateralism—shared the optimistic emphasis on worldwide democratization. In this sense the trend was bipartisan. The Clinton administration pursued a policy of international engagement and enlargement, hoping to expand the sphere of friendly market democracies at limited cost to the United States. The George W. Bush administration responded to 9/11 by embracing ambitious attempts to democratize the Greater Middle East. And the Obama administration—while dialing back on Bush’s particular emphasis—hoped to encourage greater international coordination around liberal norms through U.S.-led accommodations.

All three of these post–Cold War presidents were sincere in their broad foreign-policy goals, and all three had certain specific successes. Yet history did not end. That is to say, historically normal patterns of interstate rivalry and geopolitical competition—animated by differing ideologies, shifting power dynamics, and competing national interests—did not disappear. Instead, they simply took new forms. In particular, the rise of China; the resurgence of Russia under Vladimir Putin; and the stubborn persistence of numerous authoritarian regimes well beyond those two major powers combined to create disturbing new security challenges for the United States and its traditional allies overseas.

The Trump Phenomenon

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump had unexpected success campaigning against the Wilsonian tradition in its entirety. He argued the United States had borne disproportionate costs for its expansive world role going back many years. He maintained that multilateral free trade agreements had harmed the interest of American workers. He stated that post–Cold War U.S. military interventions had been generally botched. He insisted that America’s allies had not carried their share of the common burden with the United States. And bundling the issue of immigration into these concerns, he proposed a hard line against illegal migrants, drawing a clear line between benefits for U.S. citizens and benefits for those who are not.

Nobody knew exactly what Trump’s foreign policy would look like if put into place. Perhaps he himself did not know. Given his many off-the-cuff statements and unusual persona, there were plenty of reasons for concern.

Now three years later, liberal internationalist critics argue that the foreign-policy record of the Trump administration is one of relentless assault on the rules-based world order. In fact they regularly lump the United States government together with prominent autocracies based in Moscow, Beijing, and elsewhere as part of an overall nationalist authoritarian assault on rules-based liberal order. But setting aside the fact that American nationalism is democratically expressed—in other words, the opposite of authoritarian—there are still some profound problems with this common liberal understanding.

In actual fact, as president Trump has not dismantled either America’s alliance system or its forward presence overseas. To be sure, he has pushed U.S. allies hard on trade as well as on defense spending, and probed the underpinnings of internationalist assumptions. The forty-fifth president is no Wilsonian—far from it. Yet the Trump administration continues to maintain a range of pressure campaigns against U.S. adversaries overseas, and in many cases has escalated these campaigns relative to the Obama era. This is no comprehensive disengagement offshore. Strict non-interventionists within the Republican Party understand that very well, which is precisely why they question those same pressure campaigns. There is no misunderstanding on this point.

Trump moves up and down the escalatory ladder, trying to carve out what he views as relative material gains for the United States. A lot of observers have a hard time turning the volume down. But watching his behavior as president, there is really no more evidence that he is hell-bent on destroying what liberals describe as the “rules-based world order” any more than he is on upholding it. The concept is obviously not his primary reference point one way or the other. Rather, he is undertaking a kind of portfolio reassessment of America’s international commitments, and its outcome is not predetermined.

Agitated by this spectacle, the liberal internationalist recommendation today is essentially to return to the liberal internationalist tradition. And to be sure, there are important and interesting debates going on among U.S. liberals and progressives over whether to lean in a hawkish or dovish foreign-policy direction. Issues of defense spending, military intervention, and the precise contours of counter-terror policy are very much in play. But virtually all prominent liberal and progressive voices, whether increasingly dovish or not, agree on the fundamentals of a Wilsonian foreign-policy framework. Today’s Wilsonians argue the United States must restore the sanctity of multilateral organizations, re-enter all agreements concluded by the Obama administration, prioritize human-rights promotion, abide by liberal rules, emphasize soft power, avoid unilateral action, and proceed to solve global problems by coordinating interstate compromises through global institutions.

And yet it was the failures and frustrations of a Wilsonian framework that helped lead to the Trump phenomenon in the first place.

Looking Ahead

A more persuasive case might be to distinguish those elements of America’s internationalist legacy that have been useful, from those that have not. On balance, American national interests have been well served by a U.S.-centered alliance system that deters major authoritarian adversaries and keeps them at bay. This alliance system involves an underlying U.S. forward presence to maintain regional balances of power. Some now promise that dismantling those military alliances would create no great danger to important U.S. interests. This seems highly unlikely. A comprehensive American disengagement overseas could very well encourage increased weapons of mass destruction proliferation, terrorist advances, authoritarian aggressions, and major power warfare. And the United States would inevitably be pulled back in, at even greater cost than before.

America’s alliance system—along with its supporting armed forces—also helps to buttress relatively open trading arrangements of mutual benefit to leading democracies. And those benefits are strategic as well as economic.

Having said that, there are numerous aspects of the Wilsonian foreign-policy tradition, strictly speaking, that really have proven to be dysfunctional. Some of these dysfunctional features have become increasingly obvious since the end of the Cold War. Others go back to Woodrow Wilson himself.

In other words, Henry Cabot Lodge had a point.

The Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that the international system can be utterly transformed, from darkness into light, if only Americans bind themselves to a range of commitments that are universal, multilateral, and global. In reality however, for all the progress of the last century, the basic nature of international politics still shows some stubborn continuities with previous eras. Independent nation-states—whether democratic or not—still pursue their own particular interests, in the knowledge that no global institution will defend them with equal intensity. Nor are leading authoritarian nation-states interested to bind themselves under liberal rules. On the contrary, they look to see America bound, and themselves free to act however they see fit.

The Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that multilateral institutions can act as a kind of silver bullet for every pressing international security challenge. But multilateral organizations, while sometimes useful, have no such magical power. The most pressing security challenges are not problems of legality. In many cases of utmost interest, multilateral institutions work at the perimeter of international power politics, not the center, and their claims are frequently unenforced. Nor is it clear why global organizations populated by numerous unelected dictatorships should lay claim to any superior morality over the sovereign decisions of free countries.

The Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that the world’s nation-states are ultimately on track to converge around liberal democratic norms. It encourages the belief that democracy promotion is possible pretty much anywhere, if only we try. But the past twenty years have revealed otherwise. Major authoritarian regimes have survived and in some cases flourished. Numerous dictators have been toppled. Yet chaos has often followed. As it turns out, democracy promotion is extremely difficult, and in many notable cases, the circumstances on the ground are simply not propitious.

The Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that American national sovereignty must constantly and necessarily be ceded to global multilateral arrangements. But it is perfectly reasonable for Americans to want to preserve their own independence, domestic institutions, national traditions, and particular way of life. Indeed democratic accountability demands that national self-government be preserved.

The Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that there is no great difference between authoritarian nationalism and democratic versions. But there is all the difference in the world. The totalitarian powers of the twentieth century would not have been undermined and defeated without the power of democratic nationalism arising in the United States.

The Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that almost every international interaction must be viewed as a test case of some universal liberal rule, to be articulated and—maybe—enforced. This makes it virtually impossible to weigh the costs and benefits of alternate U.S. strategies, case by case, in a sane and sensible fashion, with reference to the national interest. Indeed it appears intended to have this effect.

Finally, the Wilsonian mindset encourages the belief that U.S. armed forces can be cut, or permitted to atrophy, so long as Americans make a blizzard of multilateral treaty commitments supposedly rendering military power irrelevant.

The above mistaken assumptions, flowing from the Wilsonian mindset, are not simply conceptual failings. They are also practical ones, and have encouraged some very practical U.S. foreign-policy failures at times, most especially since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

All things considered, the end of the Wilsonian century—if that is what we are witnessing—need not represent the end of the world. It need not represent the end of democracy, since democracy and the hope for its promotion predate Woodrow Wilson. Nor need it represent the end of American alliances overseas. After all, Wilson hated what he called “special alliances.”

However, the end of the Wilsonian century can and should encourage a serious rethinking of traditional liberal assumptions regarding the nature of international politics in the coming years—and what sort of foreign policy should follow from that from an American point of view.

The recognition that world progress is not inevitable, and that historically normal patterns of international power politics have not ended, should lead to a certain long-term shift in U.S. foreign policy. The goal is not binding multilateral commitments for their own sake. Greater weight must be placed on simply working with America’s allies, and pushing back against obvious rivals and adversaries, within an internationally competitive environment.

The best response to current circumstances, in order to promote U.S. national security, is not to radically disengage. Nor is to think that America’s adversaries can be lectured into accommodation. Instead, the answer is for the United States to prepare for some steady, long-term competition with a number of serious international rivals, so as to better preserve existing democracies from a real variety of threats.

There is little point being half-hearted while protecting American primacy. But there is also no need to prioritize doctrines of regime change in most cases. The default preference for the United States should be regionally differentiated strategies of attrition, assertive containment, and peace through strength. Transformational global projects and promises from all directions must now be met with considerable skepticism. Today’s challenge is not to promote yet another Wilsonian vision, but rather to defend existing democracies. The United States is still much stronger than many believe. If it pursues tough-minded approaches, tapping into its profound capabilities, then it has the ability to outlast its adversaries and overcome them.