The Week: 52 ideas that changed the world – 4. Democracy

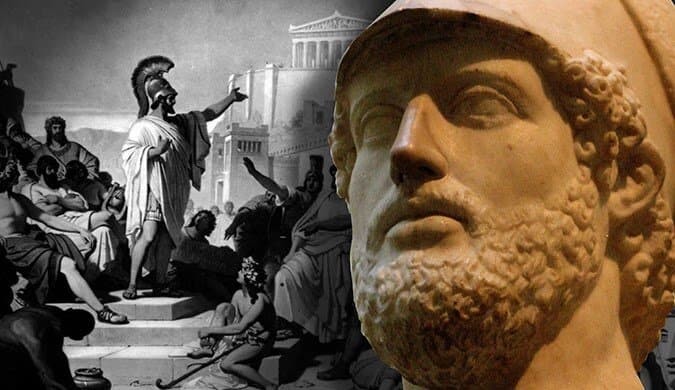

The word democracy comes from the Ancient Greek word demokratia, a combination of demos (people) and kratos (rule), and was coined to describe the system of government first formalised in Athens in the fifth century BC.

Democracy means a system in which all citizens have certain recognised political and legal rights, chiefly the right to vote and to receive equal treatment before the law.

Over the centuries, thinkers including John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Stuart Mill developed and refined the principles of democracy. In his 1859 book On Liberty, Mill “provided a philosophical foundation for some of the basic freedoms essential to a functioning democracy, such as freedom of association [and]… liberty of thought and discussion”, says the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

There are many types of democratic government – direct democracy, socialist democracy and parliamentary democracy, to name a few – but all democratic systems enshrine the right of the people to choose their leaders.

To be truly democratic, the election system must allow voters to choose freely, without fear of interference or intimidation, and with the guarantee that the count will be fair and the result upheld.

As such, countries including China, Cuba and Vietnam – where elections are held but with only one party on the ballot sheet – are not democracies, while some other countries that are democratic in practice have seen elections undermined by violence or vote tampering.

How did it develop?

The first “democracies” in the Ancient Greek city states did not resemble what we would mean by that term today, not least because only free adult males were considered citizens.

But the core principle of the Greek model – that all citizens, regardless of their wealth, power or status, should have a say in how their society was run – would go on to inspire modern democracies.

Nevertheless, for the next thousand years or so, rule by kings or a select aristocratic elite, with little or no political input from the wider population, remained the norm in most of the world.

The 17th and 18th century saw a growing discontent with these “tyrannical” forms of government across Europe and the new United States, a sentiment fuelled by increasing literacy rates and the widespread circulation of books and pamphlets advocating democratic ideals.

The English Civil War, the French Revolution and the American War of Independence are all examples of conflicts fought, to varying degrees, to establish civic freedoms, political representation and legal equality for citizens.

However, true democracy through universal suffrage – the right of every citizen to vote – was slow to arrive.

For decades in Britain, only adult male citizens who met land-holding requirements were allowed to vote, until a series of reform acts through the 19th century gradually extended the franchise. Even so, it was not until 1918 that all men in the UK were eligible to vote, and women had to wait another ten years for universal suffrage.

In the latter half of the 20th century, “decolonisation created a host of new democracies in Africa and Asia”, while “the collapse of the Soviet Union created many fledgling democracies in Central Europe”, says The Economist.

Over the same period, autocratic regimes gave way to democracy in Greece, Spain, Argentina and Brazil.

According to Pew Research data published earlier this year, “as of the end of 2017, 96 out of 167 countries with populations of at least 500,000 (57%) were democracies of some kind”.

How did it change the world?

Democracy is “the most successful political idea of the 20th century”, says The Economist.

At its heart, democracy fosters a sense of individual liberty. It “lets people speak their minds and shape their own and their children’s futures”, but also has tangible economic, political and social benefits, the magazine explains.

On average, democracies are richer, less likely to go to war and have a better record of fighting corruption than non-democracies.

All the same, the onward march of democracy across the world is far from a given. “At the heart of the new era of geopolitical competition is a struggle over the role and influence of democracy in the international order,” says US think-tank the Brooking Institute.

An obvious cause for concern for advocates of democracy is the rise of China and Russia, both of which have poor records on civic freedoms and human rights, and vested interests in undermining the influence of Western democracies.

In addition, expanding economies in parts of Asia and Africa presage a future in which a significant amount of geopolitical clout is wielded by nations currently home to imperfect or non-existent democratic processes.

However, flourishing pro-democracy movements in nations as diverse as Sudan, Hong Kong and Algeria indicate that the thirst for freedom is as strong as ever.

“The promise of democracy remains real and powerful,” says democracy watchdog Freedom House. “Not only defending it but broadening its reach is one of the great causes of our time.”

Source: The Week