Africa: 16 Days of Activism is Over, But What’s Changed for Women and Children?

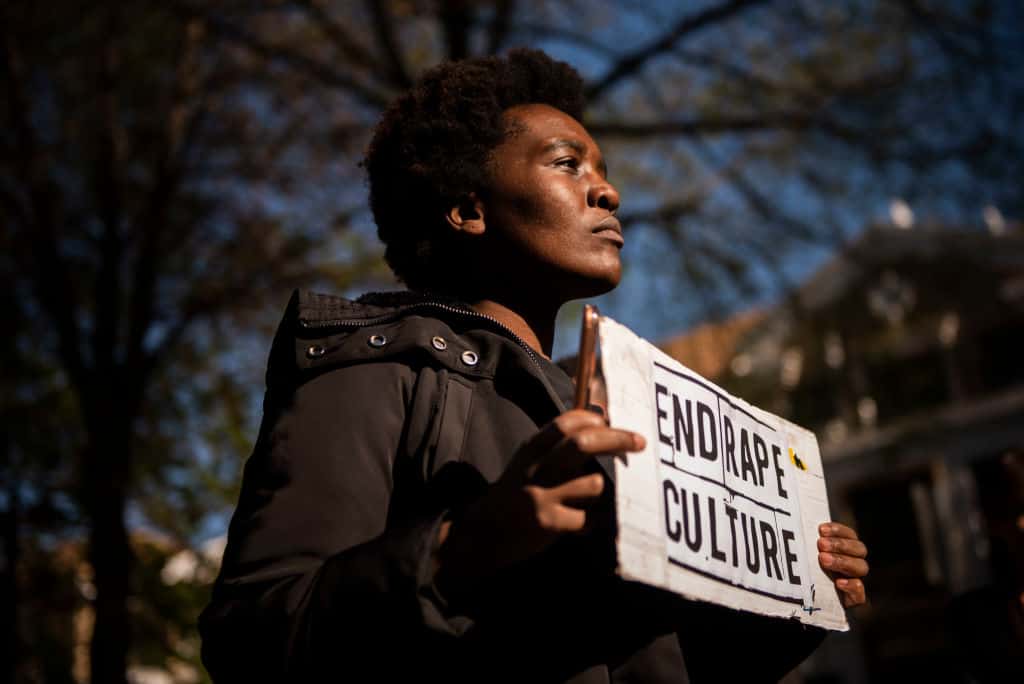

The 16 Days of Activism of No Violence Against Women and Children – an international campaign to challenge and bring an end to violence – has just ended, but the work is only beginning.

At the start of the campaign, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women, said: “If I could have one wish granted, it might well be a total end to rape. That means a significant weapon of war gone from the arsenal of conflict, the absence of a daily risk assessment for girls and women in public and private spaces, the removal of a violent assertion of power, and a far-reaching shift for our society.”

By the end of the 16 Days, Mlambo-Ngcuka expressed her shock at how the violence against women and children continued unabated during the campaign, vowing that: “Today, as we end 16 days of activism, I concur that we are not stopping the work for 365 days. We will work every day because every day a woman dies so who are we to rest.”

The reality in South Africa is one faced by 45.6% of women on the continent, 15 years and older – the highest prevalence in the world, according to this report, to have experienced intimate partner violence physical and/or sexual or non-partner sexual violence or both.

The statistics for Kenya? More than 40% of women experience lifetime physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, which is why In October, Kenya held its first 2019 National Gender Based Violence Conference to discuss how the country can move to zero gender-based violence (GBV).

According to Mum’s Village, one of the ideas that stood out in that gathering is the gaps in the processes and systems handling prevention and tackling GBV, as well as gaps in reporting, case management, responses, prosecution and the involvement of men.

The Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2014 found that 39% of married women and 9% of men aged 15 to 49 had experienced spousal, physical or sexual violence attributes the gaps to systems that aren’t strong enough, writes Serah Nderi for Mum’s Village.

The GBV centre at Kenyatta National Hospital doesn’t have a 360 degree approach to GBV, with regards to having a holistic health ( mental, physical and psychological), reporting (police involvement and case generation) under one roof. This approach by hospitals and supporting partners, would mean effective case reporting, follow up and prosecution.

Nderi says what we can do is continue talking about gender-based violence, continue to define abuse as abuse and call it out and work as a society to strengthen the systems we have.

These gaps come from having systems that aren’t strong enough. For example, Kenya’s County Gender Offices are not fully equipped to handle GBV cases. These offices are the most crucial responders at the county and grassroots level.

“If the systems in place are not enough, they can’t be trusted to respond to emergencies urgently and sufficiently enough. Whatever weakness systems have, they’re exaggerated during the emergencies,” said Olajide Demola, United Nations Population Fund’s (UNFPA) Representative for Kenya.

On November 1 and 2, 2018, the South African government in partnership with several NGOs held a national gender summit. The summit was in response to the outcry by thousands of women in South Africa, Botswana, Swaziland and Lesotho who took to the streets in August 2018 to march in protest of gender-based violence and highlight the plight of women and children.

At the end of the summit 1,200 delegates of the South African Presidential Summit against Gender-based Violence and Femicide representing survivors of gender-based violence, the government of South Africa and South African society at large signed a declaration. Collectively they reaffirmed their commitment to a united, comprehensive and effective prevention and response to gender-based violence and femicide in South Africa.

In the declaration, they also acknowledged that the psycho-social and related needs of survivors are not adequately addressed, with civil society organizations often bearing the brunt of providing care and response services in order to close service gaps in the justice system. Also acknowledging that harmful gender-based stereotypes in media reporting of women’s objectification, men’s entitlement and normative gender roles contribute to fueling the levels of gender-based violence and femicide.

Gender-based violence cannot be attributed to a single factor, but an interplay of individual, community, economic, cultural and religious factors interacting at different levels of society. All these factors ranging from gender inequalities between men and women, social constructions of hegemonic masculinity, social perceptions of what it means to be a man, normalisation of violence, and cultural practices, these are some of the finding from the Gender-Based Violence in South Africa report published in 2016.

Some of these practices like the lobola, a bride price which a prospective husband or head of his family undertakes to give to the head of a prospective wife’s family in gratitude of letting the husband marry their daughter and ukuthwala, a practice of abducting young girls and forcing them into marriage, often without the consent of their parents. These practices have been going on for decades in some African countries.

The report said: “Payment of lobola is seen as entitlement to punish women who are not subservient to their husbands. Traditional idioms such as mosadi o hwela bagadi (a woman must endure the pain in the marriage until she dies) encourage women to stay in abusive marriages. Women who decide to leave such abusive marriages are culturally mocked, called names and also seen as failures in life. Some women feel trapped in abusive marriages because of their inability to pay back the lobola Although it is not culturally expected that lobola must be paid back, some men may demand this. This leaves women with no option but to stay in abusive marriages.”

These harmful practices against women and girls can have serious consequences for the women and girls, their families and communities.The payment of lobola could easily make a man feel like he owns the woman making it very hard for a woman to leave her unhappy marriage.

In South Africa, violence or abuse is so rampant that women and young girls don’t feel safe anywhere because it takes place in public spaces, including in churches, on the streets, in the institutions of higher learning and public facilities. This led to President Cyril Ramaphosa calling for harsher sentences for any GBV crimes.

In September 2019, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced a five-point emergency plan aimed at putting a stop to gender-based violence during a joint sitting of Parliament.

“In implementing our prevention measures, we must recognise that violence against women is not a problem of women. It is a problem of men,” President Cyril Ramaphosa said.

The failure of governments to implement GBV-related policies and legislation also fuels the problem. As a result many African countries have a poor record of prosecuting gender-based violence crimes.

In Liberia the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection recorded just over 2,000 Sexual Gender-Based Violence cases from January to September 2019. Seventy percent of these are rape cases, and the majority of the cases are against minors – some as young as three months old, according to Daily Observer.

The Liberian judiciary was called on to review the bail terms on domestic violence, and reduce the hearing time of cases of domestic violence to give victims speedy justice.

“Our sisters are being raped on a daily basis and there is a need for justice. Our justice system must provide the space for perpetrators to be brought to book,” she said, but added that the system is too frustrating to seek redress,” Tarlee Dahn, a volunteer with ActionAid, told Daily Observer.

In November, Nigerian authorities launched the first nationwide register of sex offenders which will contain the names of all those prosecuted for sexual violence since 2015.

Chiemelie Ezeobi from This Day in Nigeria writes that the recent commitment by the federal government and stakeholders to end Gender-based Violence by launching a ‘Sex Offenders Register’ is a step in the right direction.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), one in four Nigerian women are sexually abused before they turn 18 with the majority of these cases not prosecuted.

“We are saying to every woman who is suffering any form of violence, be it physical, sexual or emotional, don’t stay in silence and so we are saying to them, let us break this culture of silence, come out and speak,” said Rachael Adejo-Andrew the chairperson of the Abuja chapter of the International Federation of Women Lawyers.

In the neighbouring Zimbabwe, about 1 in 3 women aged 15 to 49 have experienced physical violence and about 1 in 4 women have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15, according to United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

The country’s minister of women’s affairs, Sithembiso Nyoni, announced the establishment of a help centre for gender-based violence survivors in Chinhoyi, while 263Chat reported “an unprecedented increase in the levels of violence against women by the police”.

Changing the conversation from pointing fingers and blaming men to involving them in GBV conversations. From the conversations at Kenya School Monetary of Monetary Studies, men are more likely to participate when the conversation is more about what’s in GBV prevention for them, than them being accused of perpetuating GBV.

Gender-based violence is a grave reality in the lives of many women in Africa. Millions of women across the continent fall prey to the brutality of their male counterparts. While GBV persists in the African continent, It is important to note that it is not a problem unique to Africa. But for sustainable development, African states need to act now.

“Gender equality is more than a goal in itself. It is a precondition for meeting the challenge of reducing poverty, promoting sustainable development and building good governance.” These were the words of the late, Kofi Annan, who became the first black African Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1996.